Monday, May 2, 2011

Garuḍāsana - Part One

Monday, August 16, 2010

vīrabhadrāsana I – part one

Do you have the patience to wait

Do you have the patience to waittill your mud settles and the water is clear?

Can you remain unmoving

till the right action arises by itself?

~Tao Te Ching [1]

vīrabhadrāsana I (warrior I pose) and other warrior poses present wonderful opportunities for us to incorporate “static” practice into our daily yoga.

“There are two ways of practicing an āsana. The dynamic practice repeats the movement into the āsana and out again in rhythm with the breath. In static practice we move into and out of the pose in the same way as with the dynamic practice, but instead of staying in continual movement with the breath, we hold the pose for a certain number of breath cycles, directing our attention toward the breath, certain areas of the body, or both, depending on the goals we have for performing that particular āsana. Dynamic movements allow the body to get used to the position gently and gradually.” [2] Then, when your body is warm, you can practice static poses for strength, stability, and focus.

Complete several rounds of sūrya namaskāra (sun salutation) as a dynamic prelude to practicing vīrabhadrāsana I. As you come into vīrabhadrāsana I, notice your body and your breath, adjust to find a strong and steady stance, soften your gaze (drishti), hold the pose, and breathe. Be the warrior waiting, steady, ready, and unmoving as you wait for the mud to settle, the water to clear, and the right action to arise of itself….

Phonetic pronunciation: veer-rah-buh-drah-suh-nuh [3]

vīrabhadrā = Name of a fierce mythical warrior

āsana = Pose

Execution of the Pose [4]

• From tadāsana, step your left foot back 4 to 4 ½ feet or 1 ½ times the length of one of your legs;

• Turn the left foot 45° forward/in;

• The heel of the right foot should be in line with the heel of the left foot;

• Bend the right knee so your leg is at 90° angle and the knee is directly over your ankle;

• Inhale bringing both arms forward, up, and overhead (next to the ears) with palms facing each other;

• Keep the shoulders relaxed;

• Lengthen the spine by lifting from the floor of the pelvis;

• Engage the lower abdominal muscles;

• Press into the outer edge of the back foot, keeping the arch active and the inner left thigh muscles firm and lifted;

• The back foot is straight and actively engaged;

• Continue to lengthen upward through the spine, and keep the chest lifted and open;

• Find your drishti and maintain your relaxed gaze and your relaxed deep, quiet, smooth breath for 30 seconds to 1 minute, or longer….

• Added option: When you are ready lift the toes of both feet and drop the midline of the body lower --- this action stabilizes the ankles and the knees even more by strengthening the muscles around them, giving added focus to correcting the alignment of these joints;

• To exit, simply straighten the front leg as you step the back leg forward, lowering the arms, into tadāsana;

• Repeat on the other side.

Benefits

• Strengthens the muscles of the feet and knees

• Stabilizes the knee and ankle joints

• Stretches the hip flexors and calf muscles

• Improves balance and concentration

____________________________________

[1] Translation by Stephen Mitchell, Verse 15.

[2] T.K.V. Desikachar, The Heart of Yoga, Developing a Personal Practice (Inner Traditions International, 1995), p. 29.

[3] Stick figure instructions, pronunciation and translation provided by Mikelle Terson, Asana Learning Deck, http://www.yogablossom.com/

[4] Combined, summarized, and slightly modified from my own personal practice: Sandy Blaine, Yoga For Healthy Knees (Rodmell Press), pp. 55-56 and Olivia H. Miller, Essential Yoga, an Illustrated Guide to Over 100 Yoga Poses and Meditations (Chronicle Books, 2003), p. 64.

Saturday, August 7, 2010

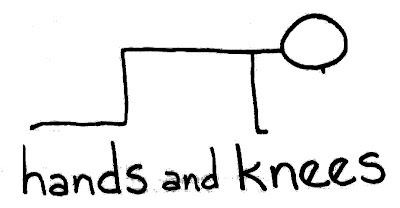

hands and knees - part one

Hands and knees pose is a foundation pose for many warm up poses and vinyāsas.

Hands and knees pose is a foundation pose for many warm up poses and vinyāsas.

In our practice of Yoga, it’s important to pay attention to 1) engaging the entire body with ease; 2) maintaining a neutral spine when we aren’t intentionally working an area of the spine in a specific way (for example, backbends and twists); 3) breathing deeply in through the nose and out through the nose and generally coordinating our breath with our movements.

This deceptively simply pose can build arm strength, leg strength, strength in the lower abdominals; and, precisely because the pose is simple, it allows us the opportunity to get a sense of what it means to engage the entire body in a pose. If you come to hands and knees and your body is not engaged, it’s not a yoga pose, it’s just hands and knees. But, when we engage our entire body and begin to breathe in through the nose and out through the nose, sensing the breath traveling the full length of the spine as it flows in and out; and, when we push our hands and knees into the earth and draw the energy of the earth up through our hands and knees, that’s a yoga pose. So, you get the idea….

* Place your hands under the shoulders/shoulder directly over the wrists

* Your fingers should be spread wide with middle fingers pointing forward

* Place your knees directly under the hips/hips over the knees

* Push into the earth with your hands

* Engage the arms

* Rotate the upper arms in so the eyes of the elbows face each other

* Though subtle, rotate the lower arms outward (this movement asks the hands to do their part in supporting the upper body in this pose)

* Engage the lower abdominal muscles

* Push the knees into the earth engaging the thighs

* Option: Turn the toes under to engage the feet and lower legs

* Crown of the head is reaching forward (not looking down and not looking up --- sensing that neutral curve of the neck)

* Sense that, at this point, you have a neutral spine from the tailbone to the crown of the head

Now close your eyes and breathe. Breathing in through the nose, the breath travels the length of the spine to your tailbone; and, breathing out through the nose, the breath travels the length of the spine back to the crown of your head. Breathe several rounds of breath until you begin to feel the energetic work of your arms and legs.

You can also sense, as you breathe in, that your hands are pulling new energy from the earth into your body, traveling up your arms, down the length of your spine, down your thighs, through the bend in your knees, down the calves, into the feet; and, on your exhale, the breath travels back the way it came and the energy goes back into the earth for recycling.

Enjoy your practice and let me know how it goes.

“The best things in life are nearest: Breath in your nostrils, light in your eyes, flowers at your feet, duties at your hand, the path of right just before you. Then do not grasp at the stars, but do life's plain, common work as it comes, certain that daily duties and daily bread are the sweetest things in life.” ~Robert Louis Stevenson

______________________________________

Thank you to my teacher, Shari Friedrichsen, for collaborating with me on how to best describe the mechanics of this pose.

Monday, July 12, 2010

Lost Yogi

Lost Yogi: Please wait patiently for me; and, I will return with the boon.

Lost Yogi: Please wait patiently for me; and, I will return with the boon. My intentions have been grand and unreachable. Posting, with credibility, various āsanas, one each week for 52 weeks, was trumped this last year by actively teaching yoga to students who wanted to learn and asked me to teach. When I return, there will be renewed commitment to my students, and to others that might stumble on the site, for regular postings that can give you the lowdown on specific yoga āsanas.

In the meantime, as I head toward the "Great Eastern Sun," I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my students.

I am sincerely grateful to all of the eager yoga students who have popped up over the last six months. You have taught me and reinforced so many things in me. The list is endless (and makes for a mushy blog) but I can sum it up this way: There was a point in my teaching when I came home so moved by each of you in class --- moved that you showed up; moved by your grace, your enthusiasm, your effort; moved by your courage and your individuality; moved by your welcoming spirits to my teaching and to the practice of yoga; moved by your tenacity; moved by your relaxed effort, your breath, and your souls following śavāsana; I was moved by you to believe that if I can live every encounter with every individual with the same respect, admiration, love, and support I feel for each of you, then I should be able to achieve a place of equanimity in this lifetime. This is my practice.

All of you are beautiful in your own unique way. I watch you and admire you; and, I am so grateful to lead you each week in the practice of yoga. Thank you for supporting me in my teaching and helping send me back to the Himalayan Institute in Pennsylvania to complete my class hours for formal certification.

As I travel, you are in my heart and in the fabric of my path and my life. I love you all.

Namasté,

Jonie

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

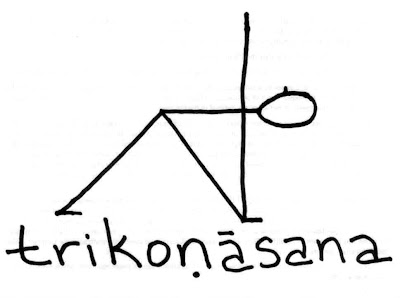

trikoṇāsana - part one

Triangle pose. Sometimes called utthita trikoṇāsana (extended triangle pose).

Triangle pose. Sometimes called utthita trikoṇāsana (extended triangle pose).“The triangle appears in many forms in the world….The qualities of a triangle are strength and the ability to support weight and resist pressure; and so the principle of the triangle is used extensively in the building industry. As you stand in Utthita Trikoṇasana, you might ask yourself how much you can support, and how well you can resist pressure.

“The tripod, used by photographers to steady the camera in order to get sharp pictures, is triangular in structure. When physical balance has been achieved in the practice of this asana, a sharper picture will emerge of the balance required in all areas of life….” [1]

Benefits: Tones the legs and strengthens the ankles; releases the hip joints as well as the groin and hamstrings; Releases the spine and spinal musculature; stretches and opens the sides of the body; opens the chest and shoulders; strengthens abdominal organs and improves digestion as it tones abdominals; aids in stress relief. [3]

Phonetic pronunciation: trih-koe-nah-suh-nuh [2]

Also, *ut-tih-tuh trih-koe-nah-suh-nuh (*u as in “put”)

utthita = extended or stretched

tri = Three

kona = Angle

āsana = Pose

Entering the Pose [3]

• From tāḍāsana (mountain pose), extend your arms out to your sides with your palms facing downward.

• Continue to focus on your breath.

• Move your legs apart while trying to bring your feet as far apart as your outstretched hands.

• Rotate the right leg out 90 degrees and then turn the left foot in slightly toward the right approximately 45 degrees. Imagine a straight line drawn back from your right heel. That line should pass through the middle of your left arch.

• Keep the front thigh muscles (quadriceps) active by gently drawing the kneecaps up.

• Imagine that your back is pressed against a wall. Work to keep the right leg rolling out (externally rotate). At the same time, keep your left hip from rolling forward by pressing it back toward the imaginary wall. This action opens the front pelvis. Keep your tailbone lengthened toward the floor.

• With your arms extending out as far as possible, exhale as you reach your right fingers out to the right side by extending your trunk from your left hip joint. Create more length in your torso by imagining your tailbone and right ribcage are moving farther apart from each other.

• Continue to focus on your breath.

• Feel the left side of your torso stretch so that your left shoulder and left hip move farther away from each other. Keep your left ribcage as parallel to the floor as possible.

• Work to keep your upper and lower body in the same plane. Continue to imagine you are standing against a wall with your left shoulder and hip rotating back.

• When you have reached as far to the right as you can comfortably, begin to lower your right hand toward the floor and reach your left fingertips toward the sky. Keep your upper and lower body in alignment.

• Feel the crown of your head reaching toward your right hand, creating as much length in your spine as possible.

• turn and look up toward your left fingers.

• Focus on balancing yourself equally over both feet as your work to keep your chest and pelvis open.

• Continue to focus on your breath.

To Come Out of the Pose [3]

Inhale and continue to press down through your legs as you bring your upper body into an upright standing position and prepare for the other side.

Cautions [3]

• Heart conditions, high blood pressure: Gaze downward

• Neck pain or injury: Continue to gaze forward without turning the neck

• Shoulder problems: Keep the top hand on the hip, and continue to rotate the shoulder back.

“…Three days of prayer, a triduum, sometimes precede spiritual occasions or practices in many religions, and include a fast or special celebrations to prepare oneself for the inner path.

“Jesus reminded his followers that where two or three are gathered together, there he would be also….

“To grow and nourish the trillium, the trinity lily, with its three large white petals, is to nourish the symbol of a pure heart, pure body and pure mind. Taking the three steps leading up to the tabernacle of the heart will allow love and compassion to flower.” [1]

Namasté,

Jonie

___________________________________________

[1] Swami Sivananda Radha, Hatha Yoga, The Hidden language: Symbols, Secrets & Metaphor (Timeless Books, 2007), pp. 79-81.

[2] Stick figure instructions, pronunciation, and translation provided by Mikelle Terson, Asana Learning Deck, http://www.yogablossom.com/

[3] Kathy Lee Kappmeier and Diane M. Ambrosini, Instructing Hatha Yoga, (Human Kinetics, 2006), pp. 81-84.

Sunday, February 21, 2010

makarāsana – part one

Benefits: Calms and focuses the mind and centers erratic energy.

Benefits: Calms and focuses the mind and centers erratic energy.Makarāsana (crocodile pose) “practiced 10 minutes a day, or better yet, 10 minutes twice a day, will bring much-needed relaxation and help establish the habit of diaphragmatic breathing. These are palliatives for emotional turmoil and vehicles for weathering the stresses of life with clarity and equilibrium. Grabbing hold of the reins of the breath to skillfully guide and direct the emotional monster from the oceanic depths, the heat of passion becomes the fire of self-transformation --- a fabulous feat for a simple but fabulous posture.” [1]

Phonetic pronunciation: muh-ku-rah-suh-nuh

“Makara: A huge sea animal, which has been taken to be the crocodile, the shark, the dolphin, but is probably a fabulous animal.” [2]

“The makara, within the second chakra, represents the ferocious, bestial power of desire which all too often may drive us to ruin. And yet, when properly directed, it is also the very current that carries us through life with joy and spontaneity and connects us to the creative power of the universe.

“How can makarāsana, commonly known as the crocodile posture, train this oceanic monster? Physically, it’s not a difficult posture; it is taught and practiced as a relaxation pose, and it is one of the best postures for working with diaphragmatic breathing. In fact, relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing are the salient features of the crocodile pose, and though subtle, these are extremely powerful techniques in the practice of yoga, as well as in managing our emotions and health in daily life.”[3]

“Makarāsana is a particularly effective relaxation pose, partly because diaphragmatic breathing facilitates relaxation, and partly because the release of tension is directed into the lower back and mid-torso where the diaphragm attaches. These tension-prone areas are affected by bad breathing habits, bad posture, and weak or tight muscles all up and down the spine and in the pelvis.” [4]

Getting Into the Pose [5]

• Lie face down

• Fold your arms, each hand on the opposite elbow

• Draw the forearms in so that the chest is slightly off the floor and

• The forehead rests on the crossed forearms

• Separate the legs at a comfortable distance (mat width) with the toes turned out

• Close your eyes

• Relax the legs, abdomen, shoulders, and face

• Turn your attention to the breath

• Feel the cleansing flow of the exhalation and the rejuvenating flow of the inhalation

Variations [6]

• There are several versions of the crocodile, each helpful and each designed to accommodate different body types and levels of flexibility.

• You may turn your feet in, with legs resting relatively close together, or

• Turn them out, separating the legs until the inner thighs rest comfortably on the floor.

• Rest your forehead on your folded forearms, elevating the upper chest slightly off the floor.

• If your shoulders or arms are uncomfortable, you may prop your upper body with cushions or a blanket (drape your chin over the cushion/blanket).

• You may also widen the elbows and partially open the forearms, allowing the hands to separate.

• In all cases, the abdomen rests on the floor.

Coming Out of the Posture

• The key for coming out of any yoga pose is to come out gradually and respectfully --- in a way that is comfortable, careful, and calming to your body and your mind.

• For a pose like makarāsana, the specifics of how you come out of the pose are not as important as your respect for the relaxation you’ve just created for and within yourself.

• Turn your face to one side.

• Use the palm of the hand of that side ot push upwards and rasie your shoulders.

• Place the palm of the other hand flat on the mat.

• And, come into a comfortable seated position.

__________________________________

[1] Sandra Anderson, “Makarasana, The Crocodile Pose,” from Yoga International Reprint Series, Simply Relaxing, p.11.

[2] A Classical dictionary of Hindu Mythology

[3] Sandra Anderson, “Makarasana, The Crocodile Pose,” from Yoga International Reprint Series, Simply Relaxing, p.10.

[4] Sandra Anderson, “Makarasana, The Crocodile Pose,” from Yoga International Reprint Series, Simply Relaxing, p.11

[5] Sandra Anderson and Rolf Sovik, Psy.D., Yoga, Mastering the Basics (Himalayan Institute Press, 2000), p. 20.

[6] Rolf Sovik, Psy.D., Moving Inward (Himalayan Institute Press, 2005), p. 68.

Sunday, January 31, 2010

vṛkṣāsana – part one

vṛkṣāsana (tree pose) “reminds us to our connection to the earth, which sustains and nourishes all living beings. We spend so much of our time walking on floors and pavement that our link to the earth is weakened. The Tree improves your posture and helps stabilize the pelvis, elongate the spine, strengthen the legs and ankles, and increase flexibility of the inner thigh muscles. In addition, it helps with balance and centering.” [1]

Phonetic pronunciation: vrick-shah-suh-nuh [2]

vṛkṣ = tree

āsana = pose

Execution of the Pose [1]

- Stand erect with your eyes fixed on a focal point in front of you. If it is difficult to maintain your balance, you may also perform this pose while lying on your back or with your back against a wall.

- Bear the weight of your body on your right leg by tightening the thigh muscle.

- Inhale and raise your left leg, placing the sole of the foot onto the calf muscle or inner thigh of the standing leg.

- If your foot slips, hold your ankle with one hand.

- Stretch the inner groin of the bent leg by taking the knee out to the side, aligning the knee with the hip.

- Breathe deeply.

- Once you are balanced, you may raise your arms above your head or clasp your hands in Namasté at the center of the chest.

- If you are holding onto your leg, raise your other hand to the middle of the chest or rest your open palm at the heart center.

- Hold for 8 to 10 breaths.

- Return your raised leg to the floor and lower your arms.

- Repeat on the other side.

___________________________________________

[1] Olivia H. Miller, Essential Yoga, an Illustrated Guide to Over 100 Yoga Poses and Meditations (Chronicle Books, 2003), pp. 70-71.

[2] Stick figure instructions, pronunciation and translation provided by Mikelle Terson, Asana Learning Deck, http://www.yogablossom.com/

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

apānāsana – part one

Apānāsana (knees-to-chest pose) is simple, feels really great, and gives an abundance of benefits. Try it every morning as a warm up to your day or every evening before bed and see if it doesn’t make a difference in your life.

Apānāsana (knees-to-chest pose) is simple, feels really great, and gives an abundance of benefits. Try it every morning as a warm up to your day or every evening before bed and see if it doesn’t make a difference in your life.Phonetic pronunciation: uh-pah-nah-suh-nuh [1]

apānā = vayu of lower abdomen

āsana = pose

In Sanskrit apānā means subtle energy that moves in abdominal area and controls elimination of waste products from the body. “Ayurvedic practitioners and yoga therapists often recommend this pose for the following conditions:

- Releases tension in the lower back. May be helpful for sciatic nerve pain.

- Stimulates peristalsis which helps to relieve constipation. [2]

- Author and yoga therapist Mukunda Stiles notes in his book, Structural Yoga Therapy, that holding this pose for 10 to 30 minutes may relieve back spasms.

- Often recommended for IBS (irritable bowel syndrome).” [3]

Basic Instructions [4]

- Lie on your back with your head resting comfortably on the floor. Make sure your chin is not higher than your forehead. If you feel any strain in your neck, place a folded blanket or towel under your head.

- Bend both knees and bring them to your chest.

- Wrap your arms around both shins, grasping your forearms or wrists. Lightly squeeze your legs toward your chest.

- Gently roll from side to side and in clockwise and counter-clockwise directions, massaging the lower back.

- For a variation, unfold your arms and place your hands on your knees. Part your knees slightly and make slow circles with them, massaging your hips and sacrum into the floor.

[1] Stick figure instructions, pronunciation, and translation provided by Mikelle Terson, Asana Learning Deck, http://www.yogablossom.com/

[2] Thus, often called the wind-relieving pose.

[3] http://www.the-yoga-place.com/kneestochest.html

[4] Slightly modified from Olivia H. Miller, Essential Yoga, an Illustrated Guide (Chronicle Books, 2003), p. 46.

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

adho mukha śvanāsana – part one

“[I]n Nepal, Tibet, and neighboring parts of India, dogs are respected for their role as guardians and protectors. In some parts of Nepal, dogs are associated with the Mother goddess, and even have their own special day during the fall festival of Dassehra. Some of the most famous cave temples in India, in Elephanta and Ellora, have lions guarding the entrance. These are not, however, the sleek lions of India, but creatures bearing a striking resemblance to Chinese or Tibetan Buddhist “lion dogs,” those mythological creatures who guard temples and palaces in the snowy heights of the Himalayas where Shiva makes his home, as well as on the other side of the mountains in China.” [1]

“[I]n Nepal, Tibet, and neighboring parts of India, dogs are respected for their role as guardians and protectors. In some parts of Nepal, dogs are associated with the Mother goddess, and even have their own special day during the fall festival of Dassehra. Some of the most famous cave temples in India, in Elephanta and Ellora, have lions guarding the entrance. These are not, however, the sleek lions of India, but creatures bearing a striking resemblance to Chinese or Tibetan Buddhist “lion dogs,” those mythological creatures who guard temples and palaces in the snowy heights of the Himalayas where Shiva makes his home, as well as on the other side of the mountains in China.” [1]Phonetic pronunciation: uh-doe mu*-kuh shvuh-nah-suh-nuh (*u as in “put”) [2]

adho = downward

mukha = face

svan = dog

āsana = pose

Pose Benefits [3]

• Develops suppleness and strength in the arms and shoulders

• Elongates the spine

• Creates greater flexibility in the hamstrings and calves

• Helps calm the nervous system

Embodying the Pose [4]

• Start on all fours

• Palms spread

• Hands in line with your shoulders

• Tuck your toes

• Inhale

• Exhaling, lift the knees and roll your tailbone toward the ceiling

• Widen through the shoulder blades

• let the weight of the head lengthen your neck toward the floor

Sustaining the Pose [5]

- Stretch your claws – widen the hands, lengthen the fingers

- Draw the shoulders down your back

- Bring the lower tips of the shoulder blades toward the front body to open your collarbones and upper chest

- Bend your knees slightly

- Then roll the sit bones up again

- Notice if you are happier with your knees, hips, and ankles in one line, or

- With the knees slightly bent

- Imagine your spine extends to form a tail

- Stretch the tip of your tail back – does this give you a sense of more length in the spine

- Imagine that your tail curls like a chow’s – can you bring the tip of your tail to the rim of your sacrum – does this enhance your feeling of lifting the sit bones

- Are you working hard in this pose, or can you find the place of rest inside it

- Exhaling

- Come to all fours

- Bringing the weight evenly to both knees

- Or, come out of the pose by walking the feet toward the hands to standing forward bend

- Then with a flat back and hinging from the hips

- Rise up to tāḍāsana

- Hamstring injury

- Wrist problems

- Spinal disk injury

[1] Zo Newell, Downward Dogs & Warriors, Wisdom Tales for Modern Yogis (Himalayan Institute Press, 2007), p.54.

[2] Stick figure instructions, pronunciation, and translation provided by Mikelle Terson, Asana Learning Deck, http://www.yogablossom.com/

[3] Jason Crandell, "Get Down Dog," Yoga Journal, 2009 Complete Guide to Yoga at Home, May, 2008.

[6] Zo Newell, Downward Dogs & Warriors, Wisdom Tales for Modern Yogis (Himalayan Institute Press, 2007), p.55 (slightly modified).

[7] Jason Crandell, "Get Down Dog," Yoga Journal, 2009 Complete Guide to Yoga at Home, May, 2008.

Thursday, October 29, 2009

caturaṅga daṇḍāsana – part one

Practicing caturaṅga daṇḍāsana[1] (Four Limb Stick/Staff Pose) plays a vital role in doing the Sun Salutations that are central to Ashtanga and vinyasas flow yoga. The pose strengthens and tones the entire body, helps teach important alignment, and prepares you for a multitude of positions including the following:

Practicing caturaṅga daṇḍāsana[1] (Four Limb Stick/Staff Pose) plays a vital role in doing the Sun Salutations that are central to Ashtanga and vinyasas flow yoga. The pose strengthens and tones the entire body, helps teach important alignment, and prepares you for a multitude of positions including the following:Arm Balances – The upper body and lower-belly strength that you develop by practicing caturaṅga daṇḍāsana, combined with the confidence it instills, translates beautifully into the kind of power and core consciousness you need for arm balances.

Inversions - caturaṅga daṇḍāsana creates a stability in the shoulders, a sense of compactness at the center, and an alertness in the legs. These, along with attention to alignment, are crucial to doing safe inversions.

Backbends – The legs feature prominently in a healthy caturaṅga daṇḍāsana and in healthy backbends (in which the curve of the spine is evenly distributed). Learning to use the legs effectively in caturaṅga daṇḍāsana imprints this awareness, so that the legs can play an active role in your backbends.

Phonetic pronunciation: chuh-tu*-rung-guh dun-dah-suh-nuh (*u as in “put”) [2]

catur = four

anga = limb

danda = stick/staff

āsana = pose

Instructions for Knees to Floor Variation

This variation will take some of the difficulty out of the pose so that you can focus on the details that will protect your shoulders as you develop strength.

- Begin in plank pose

- See that your hands are directly underneath your shoulders, your feet hip-distance apart, and your heels stacked over your toes. Pull the navel in to engage your core.

- Extend your sternum forward as you press your heels back, so that you feel your body getting long and strong.

- Draw the front of your thighs toward the ceiling—but don’t allow the tailbone to follow, or you’ll wind up with your butt stuck up high in the air.

- Instead, release your tailbone toward your heels and notice how that makes you more compact at your center.

- Keeping your gaze on the floor, look slightly forward so that the crown of your head is a continuation of the line of your spine.

- From plank, drop your knees to the floor

- Maintain the lifted, engaged feeling in your lower belly – almost as though it were a tray carrying your lower back.

- Keep your toes tucked under so you can retain a sense of your heels pressing back.

- From here, reestablish your alignment: Inhale, drawing the heads of the shoulders up away from the floor and reemphasizing the lift in your belly as you direct the tip of your tailbone down.

- As you exhale, bend your elbows, keeping them drawn in against your sides, and slowly lower yourself toward the floor.

- Keep your body as straight as a plank of wood, neither letting your center sag nor sticking your butt up in the air.

- Make sure that as you lower yourself toward the floor, the heads of your upper arms remain at the same height as your elbows rather than dropping toward the floor.

- If you are correctly aligned, your belly will reach the floor before your chest does.

- Keep your elbows by your sides

- Pull up through your core

- And press back up to all fours.

- You’ll feel your triceps working (If you don’t, you have probably allowed your elbows to splay out, with your shoulders bearing the burden of the work).

Enjoy the practice!

___________________________________________

[1] Slightly modified from Natasha Rizopoulos’, "The Low Down" (learn to hover with grace in this character-building pose), Yoga Journal, May, 2008.

[2]Stick figure instructions, pronunciation and translation provided by Mikelle Terson, Asana Learning Deck, http://www.yogablossom.com/

Monday, October 19, 2009

dhanurāsana – part one

"In the Mahabharata[1], when Arjuna is exercising his art of archery, Drona, his teacher, asks him to focus on the eye of a distant bird. Arjuna, the master archer, sees nothing else – the rest of the world disappears – and his arrow flies precisely to the target.

"In the Mahabharata[1], when Arjuna is exercising his art of archery, Drona, his teacher, asks him to focus on the eye of a distant bird. Arjuna, the master archer, sees nothing else – the rest of the world disappears – and his arrow flies precisely to the target.“The art of archery is a perfect metaphor for training the mind. The archer has to be relaxed and concentrated. The bow itself must be strong yet flexible, and it is through tension and letting go that the arrow can fly straight and true to its target.

“I find the Bow pose a wonderful exercise for developing concentration and engaging the will. The kind of strenuous movement it demands does not just happen; we have to put in the effort. We have to want to do it. In the same way, if we want to become an instrument for the Divine [in us], we have to put in the effort.”[2]

Phonetic pronunciation: duh-nu*-rah-suh-nuh (*u as in “put”)[3]

dhanu = bow

āsana = pose

Instructions[4]

- Do not be in a rush to achieve a result in this posture. Go slowly and do not pinch your lower vertebrae.

- Lying flat on your stomach, bend your knees and bring your feet toward your buttocks.

- Reach your hands back to grab onto either your ankles or your feet. Try to keep your knees close together.

- Feel your shinbones projecting away from your seat, and at the same time, feel a lengthening from your shinbones through your second toe.

- Inhale – Feel your breastbone lengthening forward as you lift the chest up off the floor.

- Feel the thighs lengthening back, out of the hips.

- Do not be concerned with how high off the floor you come; rather, listen to your breaths.

- If your breathing becomes shallow and quick, you need to back off a little.

- If you are going to lift higher, do so on inhales, and relax into the posture on exhales.

To come out of the pose[5]

- Lower your upper body and release the legs back to the ground

- Place your hands next to your chest and press your seat back onto your heels to come into bālāsana (child’s pose).

- Breathe into the back, feeling the back rise on the inhales and fall on the exhales in order to release any tension from the lower back.

__________________________________

[1] Mahabharata is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India, the other being the Rāmāyaṇa. The epic is part of the Hindu itihāsa (literally "history"), and forms an important part of Hindu mythology. It is of immense importance to culture in the Indian subcontinent, and is a major text of Hinduism. Its discussion of human goals (dharma or duty, artha or purpose, kāma, pleasure or desire and moksha or liberation) takes place in a long-standing tradition, attempting to explain the relationship of the individual to society and the world (the nature of the 'Self') and the workings of karma. The title may be translated as "the great tale of the Bhārata dynasty". According to the Mahabharata's own testimony it is extended from a shorter version simply called Bhārata of 24,000 verses.[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahabharata

[2] Swami Lalitananda, The Inner Life of Asanas [the best of hidden language hatha yoga from ascent magazine] (Timeless Books, 2007), pp. 77-78.

[3]Pronunciation and translation provided by Mikelle Terson, Asana Learning Deck, http://www.yogablossom.com/

[4]Alan Finger with Al Bingham, YogaZone, Introduction to Yoga (Three Rivers Press, 2000), pp. 156-157.

[5] Alan Finger with Al Bingham, YogaZone, Introduction to Yoga (Three Rivers Press, 2000), p. 157.

Monday, October 12, 2009

śalabhāsana – part one

Śalabhāsana, the locust posture, “is named for the manner in which grasshoppers (locusts) move their rear ends up and down.”[1] Locusts differ from grasshoppers in that they have the ability to change their behavior and habits and can migrate over large distances. As Desert Locusts increase in number and become more crowded, they change their behavior from that of acting as an individual (solitarious) insect to that as acting as part of a group (gregarious).[2]

Śalabhāsana, the locust posture, “is named for the manner in which grasshoppers (locusts) move their rear ends up and down.”[1] Locusts differ from grasshoppers in that they have the ability to change their behavior and habits and can migrate over large distances. As Desert Locusts increase in number and become more crowded, they change their behavior from that of acting as an individual (solitarious) insect to that as acting as part of a group (gregarious).[2]The Sanskrit word yoga translated means “union,” “yoking,” or “bringing together.” Practicing śalabhāsana (the locust pose) can remind us of our ability to change behavior and habits; and, of our thriving stamina to make and survive the long journey. As our practice moves us inward, joining our physical, mental, and spiritual lives in service of the highest and true self; likewise, śalabhāsana can remind us that our yoga practice joins us in service of the community as we allow the yoking of our innermost self with the outward relationships of “the group.” The practice of yoga can create union on and off the mat, solitariously and gregariously.

Phonetic pronunciation: shuh-luh-bah-suh-nuh[3]

śalabha = grasshopper (locust)

āsana = pose

“The locust postures complement the cobras, lifting the lower part of the body rather than the upper; but they are more difficult because it is less natural and more strenuous to lift the lower extremities from a prone position than it is to lift the head and shoulders.”[4]

Experiment (cobra v. locust)[5]

- Imitate bhujaṅgāsana (cobra). Lie prone with the chin on the floor and the backs of the relaxed hands against the floor alongside the thighs. Lift the head and shoulders. Look around. Breathe. Enjoy. This exploratory gesture is very natural.

- Imitate śalabhāsana (locust). Starting in the same position, point the toes, extend the knees by tightening the quadriceps femoris muscles, and exhale. Keeping the pelvis braced, lift the thighs without bending the knees. Don’t hold your breath, and be careful not to strain the lower back. Hold. Breathe.

- Notice and contrast the relative ease in lifting the upper body and holding it there with the unfamiliarity of lifting the lower extremities and remembering to breathe while lifting and holding.

There are several versions of śalabhāsana (locust) with the advanced full locust being “one of the most demanding postures in hatha yoga.” The easiest locust posture involves lifting only one thigh at a time instead of both of them simultaneously. This version is easier than full locust because one leg stabilizes the pelvis while the other one is lifted, and this has the effect of eliminating most of the tension in the lower back.[6]

Instructions for half śalabhāsana (easy/preparatory locust)[7]

- Lie on your stomach with the chin on the floor and legs together

- Point the toes, elongating the entire body

- Arms are alongside the body

- Close the hands in a loose fist with back of fists against the floor

- Align your center by pulling the abdominal muscles inward, contracting the buttocks (gluteals), and pressing your abdomen, hips, and pubis firmly into the floor. This will lengthen your lower back and establish your hips in cat tilt.[8]

- Inhale

- Extend the right leg through the toes, and lift the leg 8-14 inches without bending the knee

- Lift firmly with the right buttock and lower back

- Avoid pressing the left knee into the floor to assist the movement

- The knees and tops of the feet face downward

- No matter how high you lift, keep both sides of the pelvis on the floor and the chin down

- Repeat 3-5 times

Practice this version of the posture until you develop sufficient strength to do the double-leg or “simple” full locust comfortably. When you are ready:

Double-leg/”Simple” śalabhāsana[10]

- Lie on your stomach as before

- Chin on the floor

- Arms alongside the body

- Backs of the fists against the floor

- If you want to make the posture more difficult, supinate the forearms and face the backs of the fists up

- Point the toes to the rear

- Tighten the gluteal muscles (buttocks)

- Keeping the knees extended and the legs no more than hip-width apart

- Inhale

- Raise both legs

- Hold and continue to breathe diaphragmatically[11]

- Then, release slowly back to the floor, relax your hands, turn your head to one side and rest

- Repeat several times

Benefits[12]: Strengthens the legs, buttocks, and lower back; massages the internal organs; stimulates the nervous system; adjusts the alignment of the pelvis; develops subtle awareness of the interrelationships among the legs, pelvis, abdomen, and lower back.

___________________________________________

[1] H. David Coulter, Anatomy of Hatha Yoga (Body and Breath, Inc. 2001), 296.

[2] "Frequently Asked Questions about Locusts", http://www.fao.org/ag/locusts/en/info/info/faq/

[3] Pronunciation and translation provided by Mikelle Terson, Asana Learning Deck, http://www.yogablossom.com/

[4] H. David Coulter, Anatomy of Hatha Yoga (Body and Breath, Inc. 2001), 296.

[5] Modified from H. David Coulter, Anatomy of Hatha Yoga (Body and Breath, Inc. 2001), 296.

[6]H. David Coulter, Anatomy of Hatha Yoga (Body and Breath, Inc. 2001), 302.

[7] Sandra Anderson and Rolf Sovik, Psy.D., Yoga, Mastering the Basics (Himalayan Institute Press, 2000), 96.

[8] Erich Schiffman, Yoga, The Spirit and Practice of Moving Into Stillness (Pocket Books, 1996), 202.

[9] See Leslie Kaminoff, “Breathing”, Yoga Anatomy (The Breathe Trust, 2007), 171.

[10] Combined and modified from H. David Coulter, Anatomy of Hatha Yoga (Body and Breath, Inc. 2001), 296 – 299 and Sandra Anderson and Rolf Sovik, Psy.D., Yoga, Mastering the Basics (Himalayan Institute Press, 2000), 96-97.

[11] See Leslie Kaminoff, “Breathing”, Yoga Anatomy (The Breathe Trust, 2007), 171.

[12] Sandra Anderson and Rolf Sovik, Psy.D., Yoga, Mastering the Basics (Himalayan Institute Press, 2000), 97.